Reading Hans Urs von Balthasar is a little like eating flavored rice cakes. You might like the experience while you're doing it, and you might think it's quite good, but you never really take anything away from it afterwards. You never really feel full. There is too much of him in it, and not enough of the voice of the Church. So far, of the books that I have read or tried to read by him, only

Cosmic Liturgy is the one I would ever own, and that is because it has some cool quotes and summaries of the thought of St. Maximus Confessor.

But the real point of this post is not to bash von Balthasar or to post once again the famous picture of him with Mickey Mouse. It is to write about the foreword to his book that I am reading now,

Presence and Thought: An Essay on the Religious Philsophy of St. Gregory of Nyssa. While I love St. Gregory of Nyssa, and his influence on how I think I have written about

here and

here, it is von Balthasar's approach that I care to focus on. It has much to do with the approach to tradition in the Patristic resourcement of last century, which I think has left us rudderless in the face of Church history and praxis.

Von Balthasar begins by stating correctly that one cannot merely transpose the thought and concerns of one epoch, (in this case, that of Greek Fathers) to another epoch such as our own. He also writes that tradition cannot be conceived as passing a baton in a relay race; the light of the Spirit is not flawlessly passed from one generation to another unchanged. Then, however, he begins to drift off into talk about more "spiritual" approaches to tradition, and how in order, "to be faithful to her mission, the Church must continually make the effort at creative invention." In this sense, our German theologian wishes the Church to read St. Gregory of Nyssa as an adult would read her diary that she wrote as an adolescent: not directly pertinent to her circumstances, but rather providing inspiration for her life that is so completely different now:

Let us read history, our history, as a living account of what we once were, with the double-edged consciousness that all of this has gone forever and that, in spite of everything, that period of youth and every moment of our lives remain mysteriously present at the wellsprings of our soul in a kind delectable eternity.Now, dear reader, you know that I am not the most reactionary person when it comes to liturgy, Church governance, theology, etc. My more reactionary sentiments often come from my counterproductive desire to be a curmudgeon, and I really don't care where people attend Mass or what prayers they say, as long as they're in the pews saying their prayers. But the old traditonalist flame ignites again whenever I read things like this. I think there is a tremendous hermeneutical hubris involved here that plagued much of the Patristic resourcement leading up to the Second Vatican Council. From Chenu, Congar, de Lubac, von Balthasar, etc. we find simultaneously a sense of wanting to return to the roots of tradition and a contempt for many things that came before them. For simplicity's sake, I will break this down into numbered objections.

1.

Why are we so different? In all of the ideas that bubble to the surface, there seems for the Vatican II peritus a sense that the sky is falling, and that this has just begun to happen. That is, our epoch is in drastic crisis, and drastic crises call for drastic measures. I'm sorry, but especially in reading a St. Gregory of Nyssa or a St. John Chrysostom, the sense I get is that things haven't really changed a bit. Even down to people being more concerned about sports than they are about what's going on in church. (Chariot races, anyone?) So why do we have to frantically start putting up new drapes and throwing furniture out the window (or in this case, adding or subtracting things from the Mass or the rosary) under some pretense the we are "different"? I don't get it.

2.

Does the Church have to increase her calcium intake? Is the Church older? Middle aged? Concerned about her 401-K plan? For all we know, these end times after the first coming of Christ could last another 2,000 years. So where's the fire at?

3.

It's okay. I'm a doctor (of theology). All of those years in a Jesuit novitiate, knowing six languages fluently, and even being well versed in all the jargon of modern philosophy make you perfectly competent to diagnose and treat all the things that "ail" the Church? Seems like you better think twice before you pick up the saw and start amputating, doc.

4.

Caught in a head trip. Most importantly, what really irks me about the advocates of the Patristic resourcement is their disregard for small "t" traditions in favor of a supposedly neglected big "T" tradition. That is, it is the idea that the former have somehow clouded and eclipsed the vitality of the latter. In other words, since the Middle Ages and the Baroque era, we have been doing it wrong, that is, up to 1962 when they started to have their say in the Church.

Maybe we can blame it on Aristotle; that whole accident vs. substance distinction has got us all into heaps of trouble. For one could envision the folks at Vatican II getting together and saying: "okay, guys, what is essential to the Mass? And what can we change to make it more relevant?" That is, what is accidental? What is essential to the Gospel, and is that getting across, or is it being clouded by Gregorian Masses for the dead and novenas to St. Jude? Is a drunken procession of Indians in Peru really what the Church Fathers had in mind when it comes to liturgy? And so on and so forth.

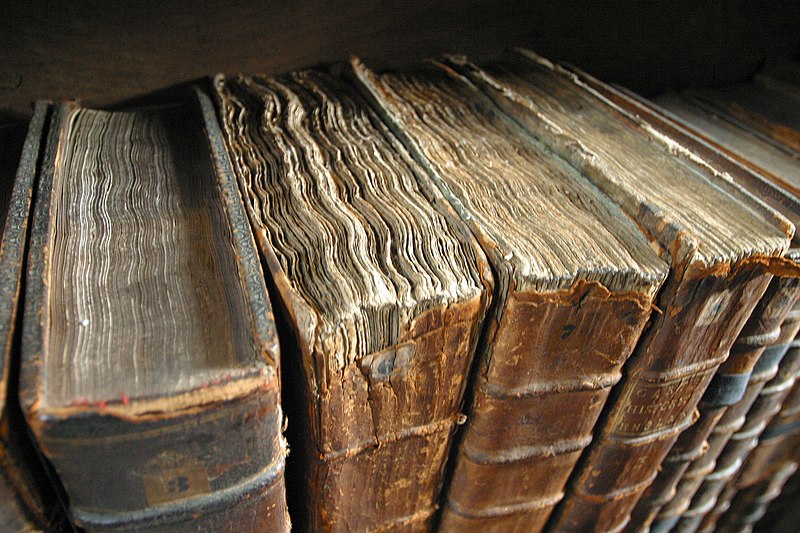

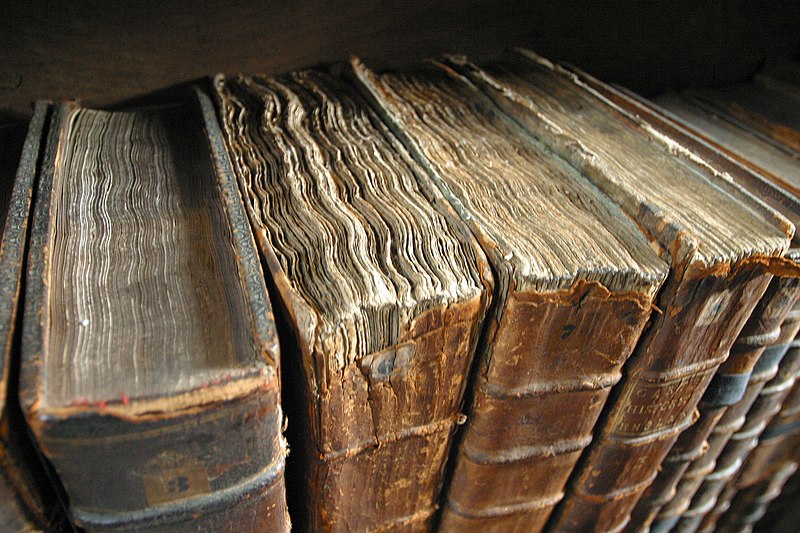

There are philosophical presuppositions to all of this, ones which I feel are highly questionable. For they all assume that in matters of Faith, we are the ones who are active in the signifying: that is, we must create a medium that expresses perfectly a clear and transparent message. It is a well defined process of transmitting information that is best left to predetermined planning and meticulous composition. I would contend, however, that we are much more passive in this process than we would care to admit. The stained glass windows, the burning candles, the statues, and the priest mumbling with his back turned to you all transmit things that we cannot express in mere words, things that are far from "accidental" to use the Peripatetic term. That is why the Church in the past, if it did intervene to change liturgy or praxis, did it slowly and almost imperceptibly, ultimately not feeling confident enough to radically alter a system that, if it didn't work well, at least worked.

(One can thus see why the historical liturgist's job can be so difficult since he has to trace small changes over an immense amount of time. One can speculate that a liturgist studying our own time would be utterly bored since everything is so variable that it would spark little interest for a keen investigator.)

In those details then lie small sparks of divinity; in those solemn and seemingly superstitious actions lie the very life blood of the Gospel as it has been read for centuries. My greatest fear is that the periti behind Vatican II unwittingly deprived the following generations of the formation in "small things" that they had as children but in their mature years deemed inessential and detrimental to the Gospel. We do not form Tradition, the devotions, processions, and mumbled prayers;

they form us. Our resourcement theologians extracted Tradition out of life and made it into a mental construct.

Even if I can live with the Pauline liturgy, the new church buildings, and the priests walking around in lay clothing, I cannot help but feel that the "hermeneutic of continuity" is a rather hollow phrase. If it doesn't look the same, it isn't the same. And no amount of "spiritual" explanations about the "signs of the times" can silence the lament of the eyes, the ears, and the soul.

For those that are good are the causes of good; and the Gods possess good essentially. They do nothing, therefore, that is unjust. Hence other causes of guilty deeds must be investigated. And if we are not able to discover these causes, it is not proper to throw away the true conception respecting the Gods, nor on account of the doubts whether these unjust deeds are performed, and how they are effected, to depart from notions concerning the Gods which are truly clear. For it is much better to acknowledge the insufficiency of our power to explain how unjust actions are perpetrated, than to admit any thing impossible or false concerning the Gods...

For those that are good are the causes of good; and the Gods possess good essentially. They do nothing, therefore, that is unjust. Hence other causes of guilty deeds must be investigated. And if we are not able to discover these causes, it is not proper to throw away the true conception respecting the Gods, nor on account of the doubts whether these unjust deeds are performed, and how they are effected, to depart from notions concerning the Gods which are truly clear. For it is much better to acknowledge the insufficiency of our power to explain how unjust actions are perpetrated, than to admit any thing impossible or false concerning the Gods...  The statue that came from Spain had the Holy Child sitting on the lap of His Mother. At one point, the statue separated itself from His Mother. No one knows exactly why this happened. The people had a throne built for the Santo Niño, where he sits even today. He is also to be found in His own Chapel in the Santuario de Plateros.

The statue that came from Spain had the Holy Child sitting on the lap of His Mother. At one point, the statue separated itself from His Mother. No one knows exactly why this happened. The people had a throne built for the Santo Niño, where he sits even today. He is also to be found in His own Chapel in the Santuario de Plateros.