Calvinist Liturgy

I found this on the Reformed Liturgical Institute Page. As a liturgy junky, I am going to give it a listen.

There is a continuous attraction, beginning with God, going to the world, and ending at last with God, an attraction which returns to the same place where it began as though in a kind of circle. -Marsilio Ficino

If You've Never Heard Coptic Chant Before....

I got this in my mailbox, so I can't resist using the Borges quote. He still is an interesting fellow. I would so like to have a cup of tea with him.

This is a good Orthodox blog with a nice aesthetic eye.

Appendix

The newest addition to my music collection is this recording of Marc-Antoine Charpentier's music for this play of Moliere. It is done, of course, by William Christie and Les Arts Florissants, which means that it is worth its weight in gold.

I had the privilege of seeing Les Arts Florissants give a presentation of Lully's Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme. It was a memorable experience. Christie, the honorary Frenchman who I believe is from the American Midwest, gave a talk before the performance. That was really cool. This guy exudes enough culture to fill a football stadium. Anything by Les Arts Florissants is worth buying and listening to over and over again.

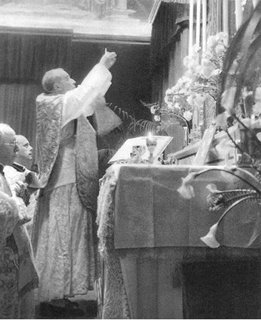

The doctrine of the sacraments is alien to the Orthodox because in the Orthodox ecclesial experience and tradition a sacrament is understood primarily as a revelation of the genuine nature of creation, of the world, which, however much it has fallen as “this world,” will remain God’s world, awaiting salvation, redemption, healing and transfiguration in a new earth and a new heaven. In other words, in the Orthodox experience a sacrament is primarily a revelation of the sacramentality of creation itself, for the world was created and given to man for conversion of creaturely life into participation in divine life. If in baptism water can become a “laver of regeneration,” if our earthly food – bread and wine – can become the body and blood of Christ, if with oil we are granted the anointment of the Holy Spirit, if, to put it briefly, everything in the world can be identified, manifested and understood as a gift of God and participation in the new life, it is because all of creation was originally summoned and destined for the fulfillment of the divine economy – “Then God will be all in all.”

The doctrine of the sacraments is alien to the Orthodox because in the Orthodox ecclesial experience and tradition a sacrament is understood primarily as a revelation of the genuine nature of creation, of the world, which, however much it has fallen as “this world,” will remain God’s world, awaiting salvation, redemption, healing and transfiguration in a new earth and a new heaven. In other words, in the Orthodox experience a sacrament is primarily a revelation of the sacramentality of creation itself, for the world was created and given to man for conversion of creaturely life into participation in divine life. If in baptism water can become a “laver of regeneration,” if our earthly food – bread and wine – can become the body and blood of Christ, if with oil we are granted the anointment of the Holy Spirit, if, to put it briefly, everything in the world can be identified, manifested and understood as a gift of God and participation in the new life, it is because all of creation was originally summoned and destined for the fulfillment of the divine economy – “Then God will be all in all.”

-Frank Senn, Christian Liturgy: Catholic and Evangelical, p.303

As a life-long Roman Catholic (with certain impromptu stops in the Christian East), I never could understand Protestantism. And I never will. It's something in my heritage; even though some of my aunts and one uncle converted to evangelical Protestantism, my blood is too Latin to understand the cold religion of the Germanic and Anglo-Saxon North. There are places, however, that I can intersect some of the ideas of Protestantism, and this quote is one of these moments of understanding.

Can anyone else observe that what Luther is saying here contradicts 99% of what Protestants believe now? If I am not too rusty in my theology, what Luther is referring to here is kerygma, the time when the Gospel is being proclaimed for the first time. The whole "turn with me, brother" attitude of all of the strictly Protestant services I have attended seemed too rationalistic and made God so distant. No wonder, not even Luther thought that things should be this way. It is the living proclamation of the Word that constitutes the Church, not the text.

The Anglican Church in Hollister had very much this feeling of proclaiming the Word. I entered Anglicanism here in a much more "High Church Protestant" setting than where I am now. Having now read this quote, now I realize what I might have experienced there. Those "Protestants" did not just read the Word of God; they "preached" it, brought it to life, and made it move about and sing. I like the Anglo-Catholicism of my church now; obviously with my background, it is much more familiar. Many times, however, I miss my Protestant congregation in Hollister.

Christianity is like music. Some days I really want to listen to Chopin, Dvorak, Debussy, or even Bruckner; this would be the equivalent of wanting to attend a Pontifical High Mass or an All-Night Vigil at a Russian Cathedral. Some days, however, a piano etude by Philip Glass, a tango by Gardel, or even a simple corrido is more to my taste; this would be the "straight '28", no frills, no lace, no incense. The latter, of course, is the bare-bones of what is acceptable (at least in my mind), but it is so simple is can surpass even the most elaborate and colorful ceremony.

Maybe I understand a little more now than I did before.

Part IX- Abyssus Abyssum Invocat

September, 2003- I went to St. Herman of Alaska Orthodox Mission in Sunnyvale not knowing what to expect. From the outside, it appeared to be a converted Protestant church with a steeple. I had just been to an Ignatius Press conference and was psyched about being Catholic, but still a little conflicted about the fact that I was going to an Eastern Catholic church and was planning on becoming an Eastern Catholic monk. I entered the church and found that it was like any other church of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia: no pews, lots of icons of impeccable taste, and a gorgeous iconostasis. I began to venerate the icons.

When I came to the icon of Our Lord in front of the iconostas, a priest came out of the sanctuary wearing a riassa and sporting a very trim haircut and beard. The first thing he said to me (and I am not making this up) was:

"You used to be a seminarian, didn't you."

I froze. Was this man clairvoyant? Did I have it written on my forehead that I had left seminary nine months earlier and would be entering a monastery in another six months?

"Yes, Father," I replied, "how did you know?"

" I used to be a Marist seminarian a long time ago."

Needless to say we talked to almost two in the morning after All-Night Vigil was over. He gave me one book, not the only or the first book on Orthodox theology I have ever read, but maybe the one that tied many themes together for me in my own mind. The book was Greek theologian Christos Yannaras' work, The Freedom of Morality, and while it has great flaws like any book, it is one of the most prophetic Christian works ever to confront modern thought.

I can here talk about various themes of the book, but that is not the point of these posts. The point is what I perceived was said, and its affect on how I believe and think. The main theme that Yannaras is trying to get across is: the Gospel is not what you think it is. That is, life in Christ is a relationship and not a system. You cannot buy off God (as I have said many times in the past), and you cannot enter into a relationship with Christ on your own terms. We can say this until we are blue in the face, but we will never understand it. The life of the "old man" of the flesh is our constantly forgetting and reminding ourselves of these things. Yannaras is trying to shake us out of this complacency in our relationship with God, Christ, the Church, and society in general.

One of Yannaras' main targets, infering from the title of the book, is modern moral theology. There is one chapter in the book where he cites that many early editions of St. John's Gospel do not include the story of the woman caught in adultery, implying that many early Christians rejected this story as false because the woman showed no sign of repentance. Yannaras uses this episode to make a key point in his book:

The ethics of the Gospel have as their aim the transfiguration of life, not merely a change in external behavior or punishment of behavior disruptive to social harmony.

I pause here now to reflect how this concept re-formed how I approach my spiritual life. In traditional Western Christianity, there is a temptation to conceive of sin as "strikes on your record" and virtue or good works as "brownie points in your favor". Since sin is an infinite offense against an infinite God, the temptation of Western spiritual practice is to focus exclusively on "not sinning" and "wracking up points" so as not to have to spend time in purgatory and enter Heaven quicker. While this is an exaggeration, it is a very real one. That is how I thought about these things when I was a teenager reading St. Alphonsus de Ligouri.

Many authors of the East, however, are very clear that this is not the case. The important thing is to be formed in the image and likeness of God, and that will almost inevitably involve falls into sin and repentance. As Yannaras writes when talking about confession:

...[T]he healing of such perversion in the sensory organs of life cannot result from binding conditions and obligations to show some objective "reform", which inevitably keep man confined to the impasse of individual effort and individual morality. It can only come through gradual understanding and dynamic experience of the truth of the mystery [of repentance], through bringing one's sins to the Church again and again until one gains real humility, and this humility encounters the love of the Church - until life does its work, and the deadened nature is raised up.

In other words, repentance and all morality is ecclesial: it is NOT about me. I am a pile of filth as an individual; as a person in communion with the Body of Christ, I am born a new creature. That is the message of Yannaras' book. And that changed how I approach my own struggles day in and day out.

The book does have its flaws. Yannaras seems to have never met a Western theologian he liked, and a phenomenological philosopher he didn't like. Some of his arguments paint the Western Church in broad, sloppy strokes, comparing the best of the East with the worst of the West. This is an unfair if very common error that Orthodox theologians commit. He also even gets to the point of accusing Chartes Cathedral of being decadent Western scholasticism in stone and stained glass; a very specious argument to say the least.

Still, it is a book that must be read. If you are Orthodox and haven't read this book, you need to buy it right now (here's a link). Western Christians should of course also read it. It will help you understand that our approach to God is a coming together of opposites that approach one another in love and trust. As Yannaras so eloquently puts it:

As the Christian explores the bottomless depths of human failure through immediate experience, he realizes the magnitude of the possibilities of love, and he dares to make the leap of repentance. Thus he meets complete acceptance in the infinity of God's love for mankind: "He who knows the weakness of human nature, the same has had experience of divine power," says St. Maximus Confessor. Salvation is when two infinite magnitudes come together: here alone does "one deep call to another."

Okay, stop what you are doing and go to this site. These are more fun photos of my former seminary posted on October 1st.

Okay, stop what you are doing and go to this site. These are more fun photos of my former seminary posted on October 1st.

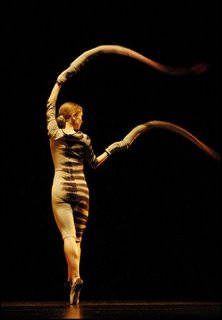

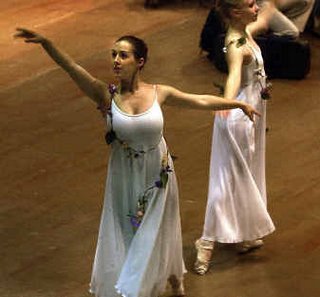

But in one way Purcell is a finer stager than Wagner: his music is full of movement, of dance. His is the easiest music in all the world to act. Only those can realize fully the truth of this who have experienced the joy of moving to Purcell's music, whether in the ballroom, or on the stage or in the garden; but especially in the garden.

But in one way Purcell is a finer stager than Wagner: his music is full of movement, of dance. His is the easiest music in all the world to act. Only those can realize fully the truth of this who have experienced the joy of moving to Purcell's music, whether in the ballroom, or on the stage or in the garden; but especially in the garden.

-Barbara Jeanne Fields, Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America

The royal headship could be maintained because Scripture would "bear" it. It rested on the plain precedents of the Old Testament and the clear indisputable teachings of the New. But for the papal headship there was only the flimsiest of biblical evidence.

G.W. Bromiley, Thomas Cranmer: Theologian, p.14