Lord and Master of my life, do not give me a spirit of sloth, idle curiosity, love of power and useless chatter. Rather accord to me, your servant, a spirit of sobriety, humility, patience and love. Yes, Lord and King, grant me to see my own faults and not to condemn my brother; for you are blessed to the ages of ages. Amen.

Lord and Master of my life, do not give me a spirit of sloth, idle curiosity, love of power and useless chatter. Rather accord to me, your servant, a spirit of sobriety, humility, patience and love. Yes, Lord and King, grant me to see my own faults and not to condemn my brother; for you are blessed to the ages of ages. Amen.This is a prayer recited by Byzantine Orthodox Christians many times during the weekdays of Lent. It is usually accompanied with about four prostrations to the ground and twelve profound bows. Aside from the poetic simplicity that this prayer exudes, the intensely physical character of its recitation shows once again how the East has maintained a more wholistic approach to the spiritual life in many aspects.

I will not try to break down the prayer and explain it line by line. For that, one would have a very good knowledge of Greek, and I have none. The translation given above is from the website maintained by Ephrem Lash.

My main focus will be on the last line, which I have always thought is the clincher. The Greek theologian Christos Yannaras in his book Freedom of Morality, gives a radical critique of the legalistic distortions that have beset modern man in his relationship with God. The most powerful moment in this book for me was when Yannaras points out that Christ forgives the woman caught in adultery without her asking explicitly for forgiveness, and how this scandalized some early Christians so much that this story was left out of some early texts.

The point of this anecdote I think was to illustrate a tension in Christianity between justice and mercy. On the one hand, we must be on the look-out so that we don't degenerate into what one Protestant theologian called "cheap grace". This is sort of the classical "are you saved?" argument of our evangelical Protestant friends. Christianity requires work, it requires struggle and reform of life. The early Church was well aware of this, perhaps too well aware of it as the ancient penitential canons of the Church often testify. The Church, in a real sense, wants her children to do better, and at times in history has pushed them to do so.

The other pole, of course, is mercy and the understanding of human weakness. This is what has led the Church to relax many of the ancient disciplines that have been seen as too hard for modern man. It can be argued quite persuasively that perhaps the modern Church has swung too far in this direction.

What, however, is the linch-pin that binds these two extremes together? Is Christianity about doing better so that we be better? Or is it the realization that we are a dunghill covered in the light white dusting of God's justice?

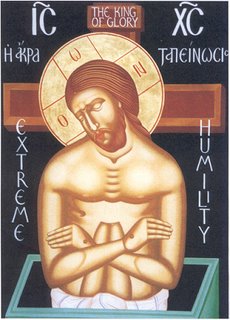

The answer is that it is neither put simply. Holiness is not what we think it is. Fr. Serphim Rose, a now deceased Orthodox monk here in the United States, was asked by people what they had to do to be holy. He replied that it was not about what you have to do, but rather who you have to BE. Holiness is not about never screwing up, nor is it about how many brownie points we can rack up in our column. It is about becoming a person, it is about acquiring a meek, humble, and loving heart. It is about being deified in Christ, acquiring His love for God and our fellow men.

This is where not judging our brother comes in. The spiritual life is not about being "holy" if holiness means what we have often thought it means. It's not about being "holy", it's about being sorry. It is about realizing how much we need God and our brother. As St. Silouan the Athonite said, "our brother is our life". It is this self-knowledge, or rather this knowledge that we are nothing without the Other and that our life is in Him, that will lead us to get rid of the barriers that block our way towards Him.

The summit here again is Love, which is always the true object of repentance.