From Glory to Glory - St. Gregory of Nyssa

Part VI- "pues fui tan alto, tan alto que le di a la caza alcance"

Part VI- "pues fui tan alto, tan alto que le di a la caza alcance"We entered through the large door facing Geary St. It was already dark, and the service was well underway. As I was told, it was all in Old Slavonic, and I was completely lost as to what was going on. Upon entering, the church was barely lit with candles, and a rather portly deacon with long hair was intoning a prayer. The choir sounded almost recorded, and I wondered if they were behind that wall in the front... where was that sound coming from?

I heeded the words of Archimandrite Anastassy: don't make trouble or they might throw you out. So I tried to be as inconspicuous as possible, standing in the back of the church like a column of salt. My friend, rather tall and with back problems, decided to sit in one of the chairs in the back of the church. I knew this was a bit of a no-no, but I said nothing.

All of a sudden, it seemed that the service ended. Everything went even darker than it already was, and a young man, probably no more than sixteen years old, went into the middle of the cathedral with a candle and a small book in hand. He began reading in that rapid-fire and serious way only Russians have mastered. Again, another service started, again the deacon, again the bodiless choir. In darkness. I looked around at the shadows bouncing off of shadows, the dimly lit icons, the rather odd looking shrine on the right side of the church to a Russian bishop. It was odd, but my life had become odd. What was I to make of all of this, this past year, this year of grace, my impending departure to South America in two weeks.....

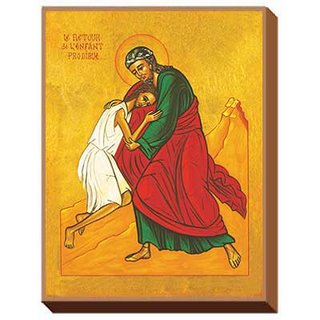

Then, the lights came on; all of them. Over the altar the imposing hands of the Virgin pleaded in supplication, with the ultimate treasure, Christ, sealed in her heart. The deacon came out and began incensing the church. All of the imposing Byzantine faces, the faces of the Body of Christ, who were slaughtered like lambs, who suffered in deserts, and kept vigil through the starless nights, all of them looked down with kindness and love, transformed by the light of Christ. And the choir.... the choir began to sing this unearthly melody, like the waves of the ocean frozen in the ethereal contemplations of angels before the world began. Frozen and moving about rapidly. Commotion above calm, color above matter.... Heaven's gates blew open. And I would never be the same again. There was no going back after this:

Praise the name of the Lord,

Praise the Lord you His servants,

Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia!

You who stand in the House of the lord

In the courts of the House of our God

Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia....

Give thanks to the God of heaven

For His mercy endures forever,

Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia....

I would sing and hear this many times over the next five years of my life; in parishes, in cathedrals, in monasteries at four in the morning. It was the Polyeleos, the "Many Mercies", one of the most powerful hymns in Byzantine liturgy. And this was the true beginning of my love affair with the Eastern Church. To tell the truth, though, she had already written me some love letters by the hand of her greatest mystic: St. Gregory of Nyssa.

Growing up Roman Catholic, I was very much affected by the spiritual ethos of Augustinianism and the ideas of merit and legal judgment. Yes, I had been baptized, and yes I knew Christ in a profound way. Coming back into the Church at twenty and living everyday in a retreat center with daily Mass and Office, I of course knew something about the Faith. It was only, however, after this encounter with the Byzantine Church, and with St. Gregory in particular, that I really felt I understood what it means to be a Christian. Indeed, it was only after reading and meditating upon this Cappadocian Father that I really felt I knew Who God was. Before, I think I was looking at the Christian mystery through a distorted lens, a lens of agendas, slogans, and party lines. Afterwards, I saw that there was so much more splendor behind all of the doctrines that I had taken for granted. I learned that often in life, you have to pursue wonder and not certainty, beauty and not systematic truth. And we will never be "there", "there" is the continuous process of getting there:

To follow God wherever He might lead is to behold God.

Beauty, however, the uncreated Beauty of God, is what most enchanted that twenty-one year old with an unsettled heart, and It continues to enchant me to this day. I would much rather look at a desert sunset, a field of wildflowers, or ocean waves crashing against volcanic stone in the spirit of prayer than read all of the theological manuals in the world. I remember when I truly understood what St. Gregory was talking about. It was during a summer thunderstorm outside of Cordoba in Argentina: the way the sky lit up at dusk without making a sound, the way those isolated mountains rose up against the great sea of the South American pampa, the whole symphony of hills and green showed me that all of creation is filled with God's light, His love and God Himself:

Pleni sunt coeli et terra, gloria tua.....

And we will never have our fill. I always imagine telling the story of St. Gregory's road, the one that we are all on, where some of us are further along, but none of us is any closer. To what? To the Beauty of God, of course! He is infinite, we are finite. He never started, but we start at some point, and the race never ends. We are running after Him, always after Him, assured that He is leading us on. This has always given me hope. For me, the spiritual life will never again be about stasis, downcast eyes, and wallowing in guilt. It is about putting your eyes to the hills, feeling the rush of the morning, arising and beginning.....

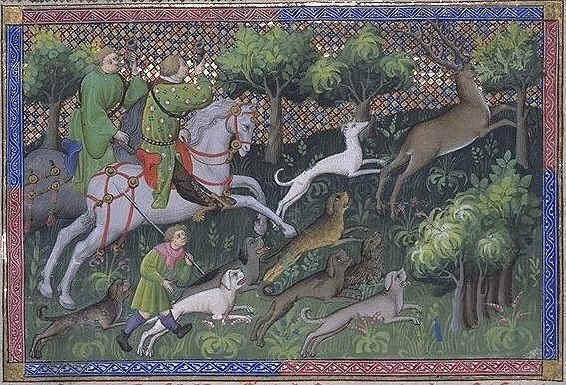

There is a poem by St. John of the Cross that I once translated into English. I don't think it was any good since I don't have it anymore. The last line is the title of this episode that I am writing. For the benefit of the monolingual gringos reading this, I will translate the last lines of the poem. The poem is about running after God, and if you have time you can Google "Tras un amoroso lance" and see if you can come up with a translation. This is how I have felt since I read St. Gregory, and I hope to feel this way tomorrow, at the moment of my death, and for all eternity:

In a manner strange

A thousand flights I passed in only one,

For in the hope of heaven

You get only what you hope for,

I hoped only for this catch

And my hoping was not in vain

For I climbed the ever ascending way

And thus gave chase to my Prey.