Enter not into a temple negligently, nor in short adore carelessly, not even though you should stand at the very doors themselves.

Enter not into a temple negligently, nor in short adore carelessly, not even though you should stand at the very doors themselves.-Iamblichus,

De Vita Pythagorica

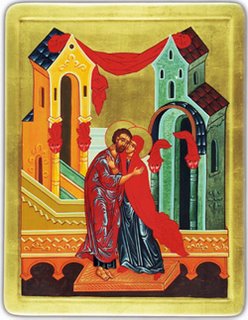

I grew up living in a religious confrontation between two worlds. One was modern Anglo-Saxon postmodern culture that regarded equality and information as the highest desirable goods. The other was the remnant of rural Mexican Catholicism that was brought to this country by my family. In this system, cycles of the Church year, respect, and duty to God and neighbor were ingrained in me from a young age. Even greeting elders was a quasi-religious ritual: we would go up as children, ask for their hand and touch it to our foreheads as if we were kissing them. Later I learned that this was also the traditional manner of greeting a priest.

When I came of age, I began to notice all around me the rituals and piety of my community. The rosary as my grandparents pray it is a catechism in rhyme concerning the most triumphalist of Catholic doctrines: purgatory, the Immaculate Conception, hell, sin, the Sacred Heart, etc. Mexican women in devotional settings have a haunting polyphony of their own that that sends shivers up your spine and tears down your face. It is a religion of the heart, one that suffers and gives all to God knowing that more often than not, they have absolutely nothing to lose.

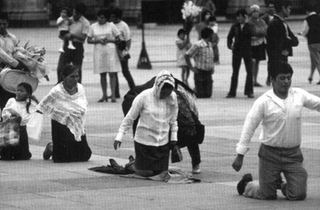

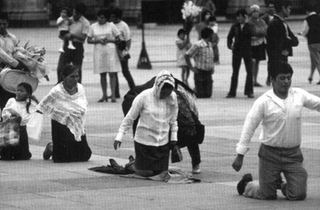

The most bizarre of rituals, though, was done by young men, often just fresh over the border from Michoacan or Oaxaca: they would enter the church from the back and crawl towards the cross on their knees. When they got to the crucifix, they said a quick prayer, kissed the corpus' feet, and left. This impressed me so much that I started doing it, much to the dismay of the parish priest.

There was always a schizophrenia there. On the one hand, these things would be done, but on the other, the most wacky liturgical things would also be done without batting an eyelash. It isn't a Spanish Mass without a guitar, altar girls were encouraged, and at my grandparents' golden anniversary Mass, the priest thought it would be a swell idea if my grandparents would give out communion. (They did, I slipped out of the church quietly at that point.) This is the conflict that I lived growing up, and to a certain extent, I am still living it. Perhaps my readers think I am crazy, pharasaical, or any number of other things, but I could never square these two worlds in my head. For the longest time, I had no idea what was going on, and I am still trying to figure it out.

*******************

It was a tree-lined dirt road about seventy miles north of the Argentine city of Cordoba. A family had cordially invited me and some other clerics to stay in a country house they had nearby. We were touring the country side around it. Unlike most of Argentina, the province of Cordoba has mountains, trees, and more to look at than just cows and grass. It reminded me much of home here on the central coast of California.

We came to a herd of goats blocking the road. Their owner, surprised to see the car, tried to get his charges out of the way, but more often than not the goats just gave him that clueless stares that only a goat can give. Finally, we were on our way, and our host said that one of our destinations was not far away.

We pulled up in front of a small cemetery with a building at the rear. Apparently, this was a site of pilgrimage once a year of gauchos from hundreds of miles around who come on horseback to honor Our Lady of..... (take your pick, there are about a thousand of them). We began to peruse the gravestones of the rather archaic and humble cemetery. Finally, we met the caretaker of the place, a woman in her early fifties and her rather bored granddaughter. Having cassocks on and a priest with us, we were honored guests in a church that seldom had clerical visitors.

The walls were all white, and I do not remember the altar. All I remember was being trapped in a religious doll house. Lace and pink hues were everywhere, spilling off the bodies of plaster saints, clashing with the dirty white walls, making the whole place rather spiritually asphixiating. It was a shrine to Hispano-Catholic kitsch, and it was so not working for me. It felt more like an old attic, a sepulcher of a doomed religion. I don't think I even tried to say a prayer in it. I just got up and left as soon as feasible.

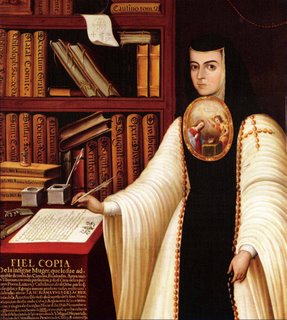

Was this a Protestant moment for me? No. I would like to think that it was that at that point I realized that the heart had been ripped out of that church (or rather the Church in general). This did not change my daily life; I was a Lefebvrist seminarian trying to keep the flame burning. That was just it: the liturgy was the heart that was missing, the soul that animated these popular devotions and made them more than some sort of baptized paganism. Without the traditional Mass, the traditional office, and traditional cycles of the Christian seasons, this religion was just a corpse. Witness, for example, the "Marian charasmaticism" of the Steubenville folk and others: they worship apparitions and spew weird heresies because they are not grounded in the traditional ethos of the Christian Church.

That, I suppose, is why I am an Anglican now in the same town I mentioned in the first part of this essay. The most profound embodiments of the religion of the Incarnation in this small town are not the statues of the Sacred Heart or the Holy Infant of Atocha, they are the genuflections, signs of the Cross, kneeling, and lifting up of hands of my Protestant, Anglican vicar, who believes whole-heartedly that he is truly communing with the Trinity. We still have a liturgy, we are not just making it up as we go along. Even if our religion is sparse in many ways, those rituals, that humble attitude we have before God and the historical witness of the Church means that we are not letting the flame die, even if my aged congregation is. That is the soul, that is what is most important. And without that, we would have absolutely nothing.

That, in the end, is my real old time religion.

(to be continued.....)